Emergence of artificial intelligence tools prompts Catholics to examine promises, pitfalls and questions about the human relational aspect

The promises and pitfalls of artificial intelligence tools prompt reflections from a Catholic perspective

At an early-morning faculty meeting at The St. Austin School, Greg Miller demonstrated to teachers the power of ChatGPT, a text-to-text website powered by artificial intelligence.

Miller typed into the chat feature a prompt, a plain-language command that tells the computer what the user wants: “I said, ‘You are a master educator. Create a short lesson plan on the virtue of prudence. It should be from a classical, Catholic perspective and for sixth-graders.’”

The teachers observed — a few quiet gasps and chuckles punctuating the silence — as the chat function churned out an entire lesson plan in 15 seconds, including sections on preparation, comparison, explanation and applications of prudence.

“Hopefully, this will save you a lot of time in your lesson planning,” Miller said to the wowed teachers.

When ChatGPT debuted last November, the AI-generated chatbot sparked excitement. But it also prompted much anxiety over the potential adverse effects, especially within education. ChatGPT traffic fell almost 10% last June compared to the previous month, with some suggesting that the end of the school year may have triggered the decrease.

Artificial intelligence tools have prompted questions from a faith perspective, especially when sharing the relational aspect of the human experience and God.

Miller worked in Catholic education in the Archdiocese of St. Louis for 17 years, including as a teacher, guidance counselor, campus minister and administrator. He recently left his role as principal at Valle Catholic High School in Ste. Genevieve and started a consulting business, Simplify AI Education, Training and Consulting, to teach educators and parents about the promises and pitfalls of artificial intelligence.

“People are scared this is going to take away everyone’s jobs,” he said, noting the effects that AI already has had on other professions including acting, writing and photography. “But we can’t avoid dealing with this. We have to be able to address this through the lens of prudence and moderation.”

The human experience

In an article featured in a seminary publication, a seminarian had written a first-person reflection on his experience of spiritual fatherhood while participating in a hospital chaplaincy internship. The article, which came from another seminary’s publication, had made the rounds among faculty at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary.

Something about the writing immediately caught the eye of Kenrick-Glennon’s president-rector, Father Paul Hoesing. “He spoke generically about his experience and more conceptually,” he recalled. “It’s something we wouldn’t expect of a second-year theologian. It was generic, vague and lacking in personal depth.”

The article had what several seminary faculty described as having a “chat-botty” feel, a term they coined to describe something that could have been generated by artificial intelligence. But it also prompted a deeper discussion throughout the academic year about the human and relational elements of a seminarian’s formation, often expressed through homilies, self-evaluations and theological reflections.

“If there’s something unique about the Catholic faith, it’s our personalism and the care of the person,” Father Hoesing said. “Each person is unique and unrepeatable, and our encounter with God is, too. Our human experience with God should not be vague and generic, but personal and concrete. We encourage the seminarians to move away from concepts focusing on ‘we’ and ‘us’ and for them to reflect in their hearts and minds how something uniquely and unrepeatably affects them.”

AI tools have generated curiosity among seminarians and faculty, but Father Hoesing said he’s not quite to the point where he can see their usefulness. A theology student’s first year of formation is marked by a propaedeutic stage, in which he eliminates technology to reorder his relationship with it and give him the freedom to enter more deliberately into relationships with God and other people.

Practically speaking, this means first-year theology students have no access to phones, tablets, computers or other electronic devices for most of the week. There is a short period on the weekend when they may use devices for reasonable contact with family and friends.

The experience aids in a seminarian’s progression of maturity, where their calling to a celibate life of priesthood allows them to invest in and love others with the heart of Jesus. “He’s starting to learn about the heart of Jesus, and then he can share it with others,” Father Hoesing said. “That’s a disciple-maker, and that’s what we are after.”

“If ChatGPT can help with relationships, then we can see about using it in the future,” Father Hoesing quipped.

“This is not going to replace us”

During his time as Valle Catholic High School’s principal, Greg Miller saw firsthand the effects of the pandemic on education, including teacher and substitute shortages. He sees how AI-powered tools can save time and help educators be more efficient in their work; students and teachers alike see its usefulness in asking questions on a range of topics.

But it’s not foolproof. The majority of AI tools have “hallucinations” or fabricated answers. “In the absence of facts in its data, it will fabricate what it thinks you want to hear, even if it’s not objectively true,” he said.

“This is not going to replace us,” Miller said at his presentation to St. Austin teachers. “We still need to be the subject matter experts, we need to be proofreading everything that it puts out. We need to be double-checking facts, and we need to do our due diligence when we use these tools.”

On the flip side, artificial intelligence has sparked concerns among student use. Miller recalled a recent presentation he gave to parents on social media, with a little information on AI tacked on to the end of his talk.

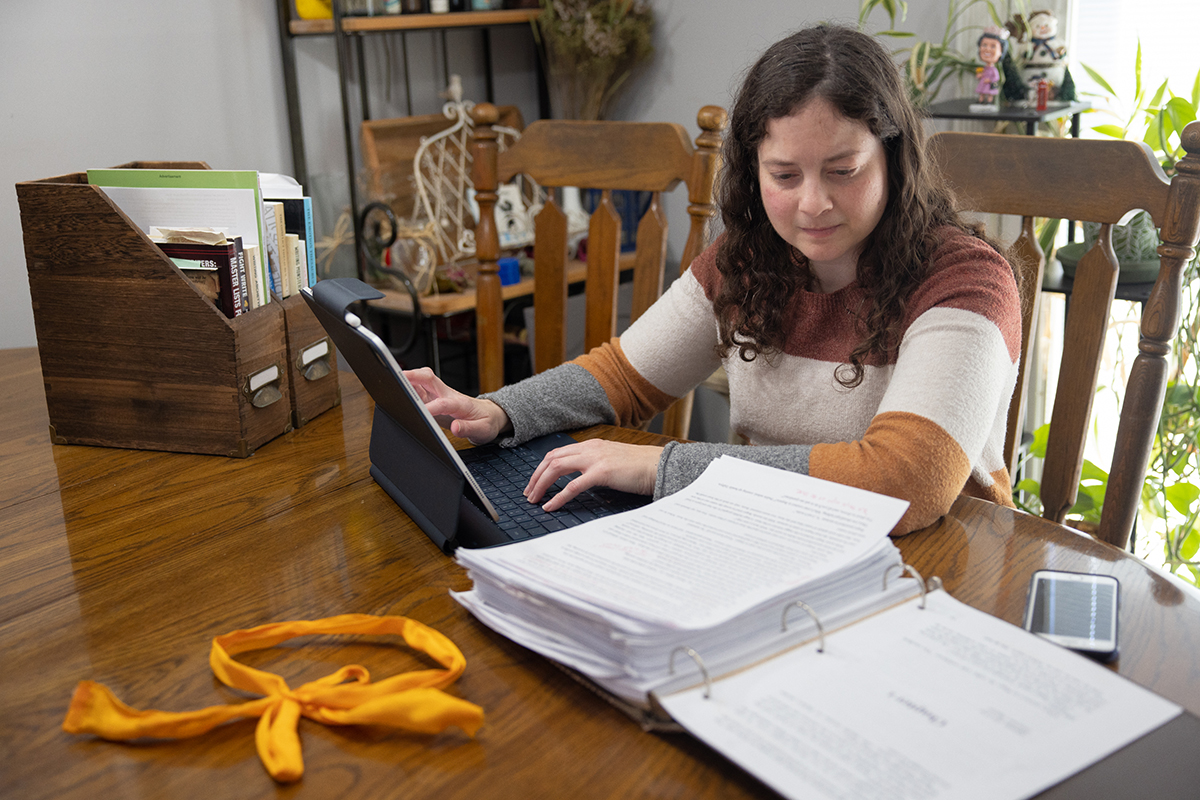

A parent in the audience said his child, a high school junior, had been accused of creating an AI-generated paper for an English composition class. The teacher claimed a program designed to detect AI-generated content flagged the paper as “100% AI-generated.”

“The father said it contained personal stories from her life, and her father saw her typing the paper herself at a kitchen table,” Miller said.

Miller doesn’t blame teachers who look out for students who are being dishonest in their work. But detector programs aren’t always accurate, either. OpenAI, ChatGPT’s creator, pulled its AI-detection tool less than six months after it debuted, citing a “low rate of accuracy.” Meanwhile, some educators have adjusted their lessons and assignments to circumvent the possibility of students using AI tools.

Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of St. Louis are taking steps to increase their understanding of artificial intelligence. The archdiocesan Office of Catholic Education and Formation is offering guidance and resources for principals on AI and its effects on education, as well as how it could be harnessed for good.

“AI is here to stay, and we want the smartest and wisest ways that it could be used in the classroom,” said Maureen Lovette, director of academic programs and planning for K-12 schools in the archdiocese. “It’s leading us to a deeper thinking in education: What are we going to ask our students to produce and demonstrate?”

Ron Tucker, vice president of academic affairs at Valle Catholic High School, said educators need professional development opportunities to understand the benefits of using it and how to monitor for inappropriate use.

“I remember a time when teachers did not want students to be able to use calculators in the classroom,” Tucker said. Later, he saw resistance to the use of word processors. “I think our work with artificial intelligence is

analogous to calculators and word processors — eventually our kids greatly benefited from using those. I think we’re going to get there (with AI). We adults just need to catch up with our kids.”

The St. Austin School takes a low-tech approach to academics, meaning students don’t use computers or other electronic devices in the classroom, said headmistress Gerry Dolan. However, she understands that this generation of students are technology natives and easily understand and adapt to developing tools.

A student’s creativity, whether through speaking, writing or other creative endeavors in the classroom, is important, Dolan said, adding that every person has God-given gifts to be used for His glory. The student-teacher relationship is an integral part of developing those gifts.

“The teacher is knowing you as a student and knowing what motivates you, how to help you reach your highest potential, to grow in virtue, knowledge and wisdom,” Dolan said. “The teachers have to know the students in order to help them grow closer to God and develop those gifts.”

Catholic artificial intelligence

Two artificial intelligence websites launched last summer focus on Church-related information, with developers saying they could be used as powerful tools for evangelization.

Magisterium AI by tech company Longbeard is trained using only documents with authentic Church information on a private database. That means it doesn’t hallucinate, or make up information, according to a press release from the developer. Citations are provided with answers. Users may ask questions and receive responses in multiple languages, including French, Spanish, Portuguese and German.

The site currently has about 4,491 magisterial documents in its database, including the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Code of Canon Law, and the General Instruction of the Roman Missal and papal encyclicals. More documents continue to be added.

The site was developed for anyone interested in Church teaching and has been used by students and teachers, parents, priests, deacons, religious and researchers. “Having worked in the Office of Spiritual Affairs at the Archdiocese of Toronto before founding Longbeard, I can tell you a tool like this would have made my job a lot easier,” founder and CEO Matthew Sanders said in the press release.

Another AI-powered site, Catholic Chat, is trained on the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Tech company Fivable developed the site as an interactive platform to allow users to engage with the Catechism easily. The site offers three levels of engagement: Child, “Simple and easy to understand teaching”; Adult, “Thoughtful answers for inquiring minds”; and Scholar, “All the details. No stone left unturned.”

“Though it will never replace a teacher or a parent, Catholic Chat does provide a place where the faithful can engage with a text that can seem daunting or unfamiliar to many,” Bishop Frank Caggiano of the Diocese of Bridgeport, Connecticut, said in a statement. “Families can use it to start a conversation about any element of the faith. Teachers can use it to ensure what they teach is the truth. Students can use it to look up questions about their faith. Even clergy can use it to infuse a little bit of the Catechism into their homilies at Sunday Mass.”

At an early-morning faculty meeting at The St. Austin School, Greg Miller demonstrated to teachers the power of ChatGPT, a text-to-text website powered by artificial intelligence. Miller typed into the … Emergence of artificial intelligence tools prompts Catholics to examine promises, pitfalls and questions about the human relational aspect

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.