Catholic sisters who participated in 1965 voting rights marches recall experiences of solidarity

Catholic sisters who participated in 1965 voting rights marches recall experiences in Selma

Catholic sisters who marched for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, 60 years ago agree that social justice isn’t a solitary pursuit but requires solidarity and a shared purpose.

Several women religious who went to Selma in March 1965 to advocate for voting rights for African Americans shared their reflections March 15 at a panel discussion and screening of the 2007 PBS documentary, “Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness for Change,” held at St. Joseph’s Academy. The documentary and supporting archives are featured on a new website, sistersofselma.org, which was unveiled at the gathering.

Sister Mary Antona Ebo, FSM, spoke during the march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Sister Mary Antona said, “I feel privileged to come to Selma. I feel every citizen has a right to vote.”

“Silence is not an option in seeking justice,” said Sister Barbara Moore, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet who attended with a contingent from Kansas City and was one of two Black nuns who participated in the marches. (The other was the late Sister Mary Antona Ebo, FSM, who went with the group from St. Louis.) “(It’s) trying to use the proper means of communication, the proper channels of communication, but to speak up when I feel there’s a need, and appropriately — most of the time,” she said to applause and some laughter.

Other panelists included Sister Rosemary Flanigan, another Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet who was part of the 50-member delegation organized by the Archdiocese of St. Louis’ Human Rights Commission; Sister Barbara Lum, a Sister of St. Joseph of Rochester and nurse who cared for civil rights activists injured during the historic “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma; documentary filmmaker Jayasri (Joyce) Hart; and Claire Vatterott Hundelt, whose father Charles F. Vatterott Jr. helped make the sisters’ historic journey possible.

The sisters who attended were answering Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for the support of clergy and others following Bloody Sunday. Thousands of people from a variety of faith backgrounds, Black and white, joined in the efforts. Those who listened to the sisters’ experiences were encouraged to advocate for racial justice today — not just in word but in action.

“We are a divided nation when it comes to the matter of race,” Sister Rosemary Flanigan said. “We people who are trying to act well have a personal responsibility to help overcome that divisiveness in our society. I don’t think we can go to bed at night and sleep well if we haven’t worked somehow that day to overcome racism in our society.”

Sister Barbara Lum, who worked as a nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma from 1958-68, was impacted by the shooting death of Jimmie Lee Jackson by an Alabama state trooper and whose death inspired the Selma to Montgomery marches. Jackson was treated at Good Samaritan, one of only a few hospitals in the area that took Black patients.

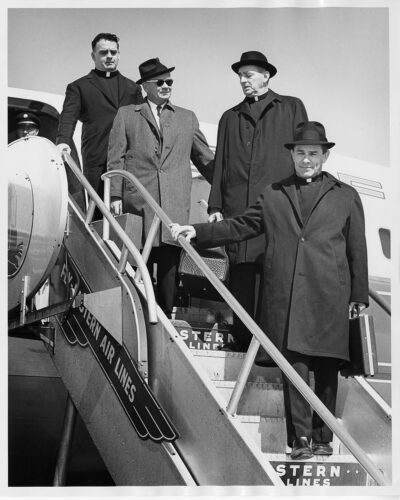

Men returned from Selma at the St. Louis Airport in 1965.

“I made rounds every day in the hospital, so each day when I would come into his room, he would put his hand out, take my hand and say to me, ‘Sister, don’t you think this is a high price to pay for freedom?’” she recalled.

Claire Vatterott Hundelt described her father’s involvement in the effort, which included funding the delegations from St. Louis and Kansas City that flew to Selma. Charles Vatterott also joined the marchers and brought along a suitcase of cash to use as bail money in case anyone was arrested.

Cardinal Joseph E. Ritter, who was responding to Dr. King’s call, found an ally in Vatterott, who had stood up against racial injustice for years and whose family continues to do so through the Vatterott Foundation and other organizations. In just 36 hours, Vatterott helped fill two planes — one from St. Louis and another from Kansas City — with priests, nuns, rabbis and Protestant pastors.

As a member of the Jesuit Manresan Society, Vatterott wrote papers on a number of topics, including racial justice. In one of them, he described it as “an urgent call to white Americans to help our colored brethren to have equality,” Vatterott Hundelt said. “He wrote that instead of following a ‘we are safe, it doesn’t concern us’ attitude, we have a responsibility, as Christ taught us, that all people are created equal and possess inherent dignity.”

Some of the St. Louis contingent was at the front of the protest that took place on March 10, 1965. The marchers had walked about a block when they were stopped by Mayor Joseph T. Smitherman and police. But they gave witness as to why they were in Selma. Sister Antona Ebo famously spoke “as a Negro” for voting rights for all. And Sister Rosemary Flanigan refused a gentleman’s offer to kneel on his coat in prayer because she wanted to go home with the dust of Selma on her habit.

Vatterott later returned to Selma in the following weeks to present a relic of St. Martin de Porres to the family of Rev. James Reeb, who was killed while participating in the Selma to Montgomery marches. He also joined the thousands of people who triumphantly marched 54 miles over five days from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery.

A few months later, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law on Aug. 6, 1965.

>> Sisters of Selma

The Carondelet Consolidated Archives of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet has launched a new website sistersofselma.org featuring archives of the efforts of Catholic sisters and other activists who participated in the 1965 civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama.

The site includes a link to the 2007 PBS documentary, “Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness for Change,” which highlights the efforts of Catholic sisters who answered Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to march in Selma for voting rights for African Americans.

The site also includes biographies of sisters in the documentary and those who had a part in the making of the film, as well as materials from the documentary’s archives, including clips of interviews, personal correspondence and photos.

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.