Sacred artist sees her vocation as leading us to God

Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs: Through the visible world we see the invisible

In churches, sacred art functions as an extension of the sacrifice of the Mass.

Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs understands her role as a sacred artist as a gift that requires trust in God.

“Christ sacrifices Himself to the Father in the Spirit through the action of His priest, but everything else on and around the altar is at once offered up with Christ as the first fruits of human effort,” Thompson-Briggs said. “We have the duty and the privilege to offer the very best to God our Father. At the same time, sacred art — the chalice, the vestments, the altarpiece — expresses the reality and the sublimity of Christ’s sacrifice to those present, helping the doubter to believe, and helping the believer to pray. We are all poor sinners, half-blinded by original and actual sin; we need visible and audible beauty to help us see the glory of God.”

Those with the means have a special duty to commission sacred art, she said, as an act of charity to both God and neighbor. “We often marvel at an achievement like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling without remembering that it would never have existed without a patron like Pope Julius II, who also started the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica. The creation of great art requires not only great artists but great patrons.”

She calls the liturgical year a source of inspiration and happiness and prioritizes daily Mass at St. Francis de Sales Oratory, where she and her husband, Andrew, are parishioners. They alternate mornings of attending Mass and caring for their three children.

Thompson-Briggs sees each commission she receives as an opportunity to learn more about the faith because of the research it requires. The Holy Spirit allows it to happen, she said.

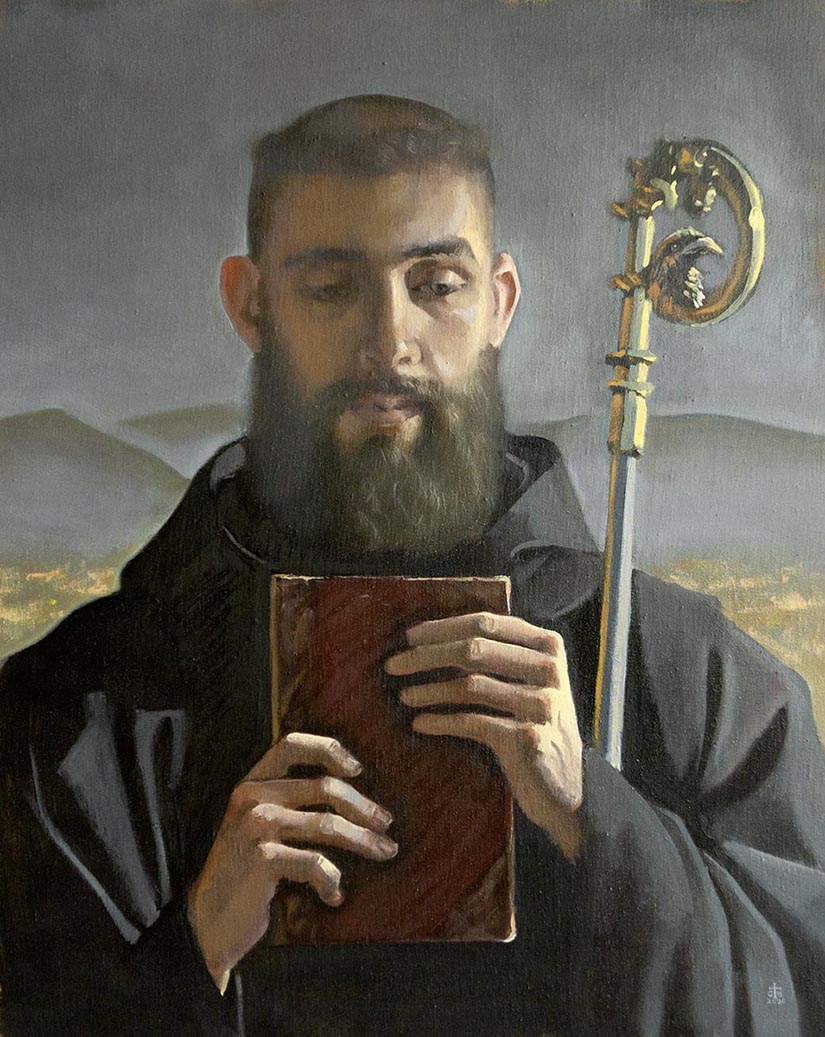

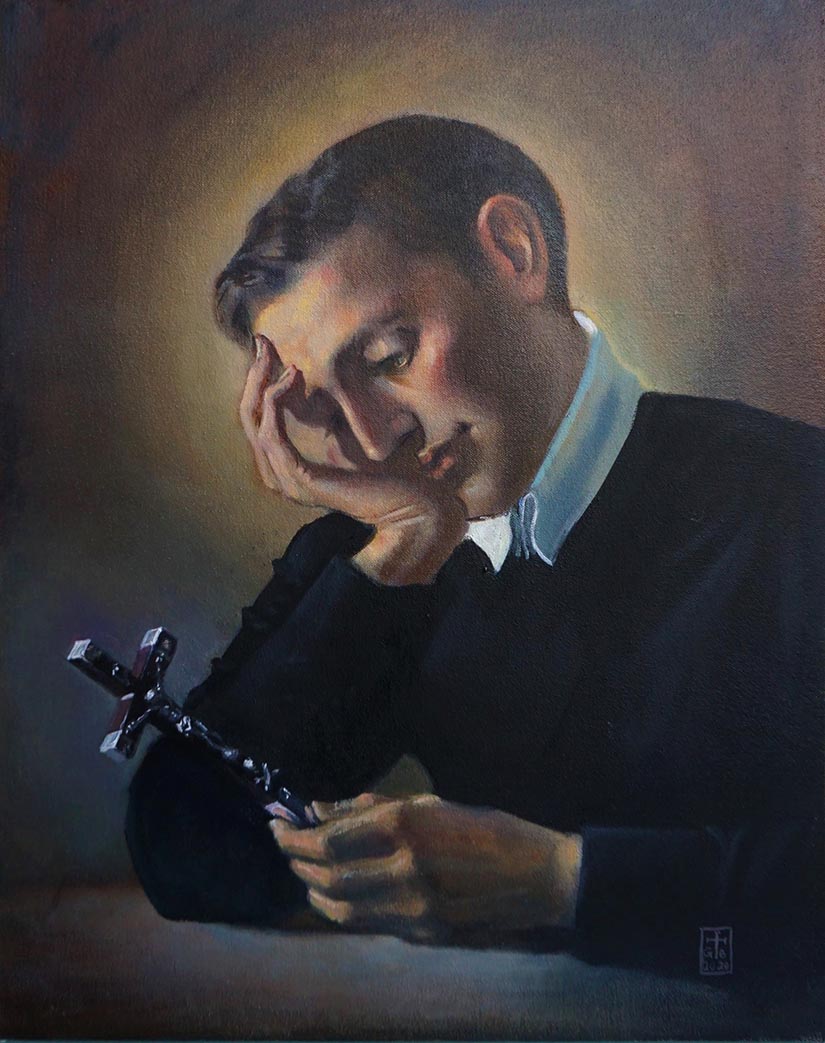

She recently worked on a portrait of St. Gerard Majella holding a cross. Before that were paintings of the Sacred Heart and Immaculate Heart of Mary as well as a painting titled “First Mass in Wyoming.”

A stay-at-home mom and business owner, Thompson-Briggs also helps young artists and their families.

Thompson-Briggs answered a few questions about her work in sacred art.

>> Why did you focus on sacred art in the Western tradition? And why is it important to reveal the glory of God through art today?

Today, most Christians are familiar with what a Byzantine icon is, and it is not uncommon to see a Western saint depicted in a Byzantine manner. Unfortunately, at the same time that the riches of

the Church’s East were being rediscovered, the traditions proper to the West were being jettisoned. I see my work as part of a larger effort to restore the patrimony of Latin Christendom. In particular, I am trying to work in the Renaissance and Baroque tradition, which I think best gives form to the Thomistic doctrine that grace builds on nature. The great Renaissance and Baroque artists paid painstaking attention to the visible world because they understood that it is through the visible that we come to know the invisible.

Restoring the beauty of worship is first of all a duty to God and an expression of our love for Him. Secondly, the patronage and creation of sacred art is an act of charity toward our neighbor, since true beauty is a reflection of God and leads us back to Him. Many of our contemporaries, I am convinced, do not recognize the truth of the Faith because they have not seen its beauty. This beauty is first of all the beauty of holiness, but as human beings we need to see that beauty incarnate in material realities. That’s how God created us and why He became man.

Why are you so attracted to portraits of saints and how do you go about it?

It is a great blessing to be able to paint a saint. I usually begin by reading about the saint’s life and reviewing the depictions of the saint in art history. One of the truths that always strikes me in studying and painting a saint is how sanctity makes a person more distinctive. I think sometimes there’s a temptation to think that all the saints are alike or that the process of sanctification involves a loss of self. To the contrary, I see again and again in the lives of the saints that allowing God to make us holy is how we become who we really are.

Why do you enjoy putting a Catholic face out in social media?

The popularity of the Twitter account (@GTBsacredart) surprised me. I’ve made many connections with fellow artists, patrons and supporters through it. The platform helps me to involve others in the creative process. I post pictures and thoughts about a project as I work on it, and followers have a chance to weigh in and see it take shape. Some users have said they’ve been inspired by seeing my creative process to dip into or back into making art themselves; that’s very gratifying. Even more gratifying is the engagement from people who find my art conducive to prayer. That’s half the measure of good sacred art: Does it promote prayer?

Why and in what ways are you reaching out to young artists?

As a young person, I had difficulty finding good art instruction. There is a lot of “art instruction” for children that is really just about either crafts or self-expression — not real training of the eye and hand. I am always happy to offer advice and ideas to parents who suspect one of their children may have a vocation in the arts.

Now that I am a mother myself, I understand the near-impossibility that other young mothers face when they try to find time to create art. Although one must fulfill the duties of being a wife and mother first, art is serious business and is worth making time for. I try to encourage and mentor artists who are tempted to set everything aside for a decade or two while they raise their children. The only way I make any art with three children under age 5 is because I have such a supportive spouse.

How does your background in science and engineering figure into your work as an artist?

Although I always wanted to be an artist, it was clear to me by high school that our society prizes math and science over art. I knew that if I studied STEM subjects, I could have human respect and a nice paycheck. Although I wasn’t much interested in the subject matter, I forced myself to get a master’s degree in engineering systems. After forcing myself to work another nine months, I realized that human respect

and a paycheck is not enough compensation for ignoring one’s true vocation. At that point, I reoriented my life toward studying art and taught college-level mathematics on the side as an adjunct professor. Surprisingly, I grew to love and appreciate the beauty of mathematics and enjoyed passing it on to others — especially artists. Now, I find that I often meditate on how light travels through a particular medium and how to render it. If I hadn’t studied optics, I know that I could not have the same insight. Additionally, I know that my background in mathematics gives me a sensitivity to structure and order.

How did you get involved in the painting for Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI?

A priest who had previously commissioned artworks from me told me he was heading to Rome to present a project of his to the pope emeritus and wished to offer a gift, perhaps a painting of St. Augustine. It was a dream commission for me, because Pope Benedict in his words and in his actions offered an elegant defense of the importance of beauty. The priest was leaving for Rome in only a few weeks, so I selected fast-drying watercolor as a medium. I had to scramble to assemble props and a model, but it was impressive how eagerly people offered help when they learned that the painting was destined for Pope Benedict. An Augustinian priory lent a habit, the diocesan archivist lent a miter and pontifical gloves, my pastor lent a cope, and a kindly parishioner loaned his beard. It all came together very quickly.

>> Sacred art in churches, public places

Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs and her family moved to St. Louis in January 2019, where they have been impressed with the region’s vibrant Catholic culture. Last summer she completed a nearly 9-foot painting of the Ascension for Ascension Parish in

Chesterfield.

“I am so grateful to Father (Thomas) Molini, the pastor, for giving me the opportunity to work on a large scale. Personally, I feel drawn toward large-scale works, and I think they have an important religious and social function as well. A few of my smaller paintings are in private collections around St. Louis,” she said.

The 2000 U.S. Catholic bishops’ guidelines, “Built of Living Stones: Art, Architecture, and Worship,” state that “every object used in the Liturgy (vesture, books, vessels, candles, etc.), every focal point in the sanctuary (altar, ambo, chair, tabernacle, font, ambry, etc.), and every work of art in the church (statues, glass, sacred images, etc.) can lead us to the Divine, because Christian beauty manifests itself ‘as an echo of God’s own creative act’ (BLS, no. 145), and therefore should reflect the best of our artistic heritage.”

For more information or to see Thompson-Briggs’ art, visit gwyneththompsonbriggs.com/about.

>> Noble mission

Sacred art is called “a great and noble mission,” one that is difficult given a culture that is not explicitly Christian.

It’s much harder today for the artist to do that noble mission than 300 years ago, said Lawrence Feingold, associate professor of theology and philosophy at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary. “It’s more important that there be images, and that goes for all the arts. Classically, painting has been a great way.”

Feingold said sacred art is important because “we come to know about spiritual things through our imagination, through our senses.”

Sacred art “helps ‘translate’ Divine revelation into ways we can see,” Feingold said, and every generation and culture needs to do it.

St. John Paul II wrote a letter to artists in 1999 in which he said the Church needs art. Art “must make perceptible, and as far as possible attractive, the world of the spirit, of the invisible, of God,” he wrote, adding an invitation “to rediscover the depth of the spiritual and religious dimension which has been typical of art in its noblest forms in every age.”

Sacred art is true and beautiful when its form corresponds to its particular vocation: evoking and glorifying, in faith and adoration, the transcendent mystery of God — the surpassing invisible beauty of truth and love visible in Christ, who “reflects the glory of God and bears the very stamp of his nature,” in whom “the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily.” This spiritual beauty of God is reflected in the most holy Virgin Mother of God, the angels, and saints. Genuine sacred art draws man to adoration, to prayer, and to the love of God, Creator and Savior, the Holy One and Sanctifier.

In churches, sacred art functions as an extension of the sacrifice of the Mass. Gwyneth Thompson-Briggs understands her role as a sacred artist as a gift that requires trust in … Sacred artist sees her vocation as leading us to God

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.