Faith and science closely linked

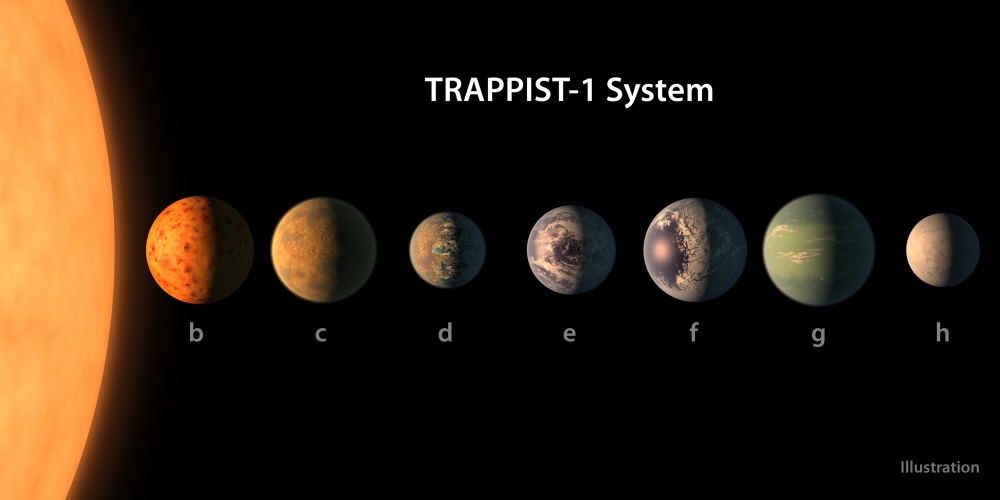

Recent headlines about the TRAPPIST-1 solar system and its seven Earth-sized planets have created quite a buzz among astrophysicists, astronomy lovers and the general population.

Surrounding a dwarf star, the system is relatively close at 40 light years from earth, and three of the planets are in the so-called habitable zone, which means a TRAPPIST-1 planet “easily could have developed a life form,” Jesuit Father Robert J. Spitzer said Feb. 27 at Kenrick-Glennon Seminary.

With an important caveat.

“An intelligent life form like ours is an all together different question simply because of the transcendental features of human intelligence, which may well require a soul,” he said before delivering the fifth annual Cardinal Glennon lecture. “God has to be part of the process in order to get that sort of intelligence.”

His plan for such a possibility?

“If aliens … are desiring perfect, unconditional truth, love, beauty and they’re self-aware and capable of mathematics at a trans-algorithmic level, I’d probably figure they’ve got a soul … in which case I’d probably evangelize them and baptize them,” he said, with a laugh. “If so, God must have created the soul. I really don’t believe (a soul) could come out of any organic matter.”

The discovery of planets in the habitable zone of TRAPPIST-1 further calls into question the Genesis creation story — God creating the heavens, earth and humans in six days and resting on the seventh, which already has been negated by the 13.8-million year-old universe presented by the Big Bang Theory.

However, Genesis isn’t a literal presentation of God’s creation of the universe and hasn’t been for 67 years. Pope Pius XII made that clear with his encyclical, “Humani Generis,” in 1950.

“The point of the Bible is the sacred truths necessary for salvation,” Father Spitzer said. “It’s not to give an accurate and physical description and explanation of the universe as we know it; that’s the job of science. Science uses a series of tools that the Bible doesn’t use, including mathematical tools, empirical tools, measuring devices.”

Bible authors neither had such items nor knew of them either.

“It would have been rather odd of God to whisper (scientific terms) to the biblical author 600 years before Jesus, saying ‘once upon a time …'” he said. “The poor biblical author would be going, ‘What?’ God has to speak to the biblical author in the way he’s going hear it — in his culture, in the time in which he’s living.

“Genesis has so many important revelations, but science is not one of the points God is trying to make.”

However, three aspects of Genesis do correlate with accepted scientific theory.

“The first one is, ‘Let there be light’ on the first day; wow, that corresponds very easily and nicely with the Big Bang Theory,” he said. “The second thing is the idea of complexification intimated by Genesis, that is quite accurate, and finally, human beings emerging as the final product. There’s self-reflectivity requiring a soul. That’s amazing stuff.”

Developed by Father Georges Lemaitre in the 1920s and endorsed by Albert Einstein, the Big Bang Theory points to the universe having a finite, specific beginning. There’s no evidence of anything before, so out of that nothingness, God must have created the universe — nothing became something, and only a metaphysical God could have created something from nothing.

In addition, if any of the variables would have been off by just a tiny bit, physical reality as we know it could not have evolved. So, an intelligent God must have included the designs for life in the Big Bang.

Catholic priests and/or scientists have espoused these beliefs over the centuries with numerous significant discoveries and insights. However, in this day and age, popular culture is mostly devoid of the linkage between Catholics and science.

“The culture has provided a big huge myth about the Church being antagonistic to science,” said Father Spitzer, noting that numerous Catholic clerics rank among the greats in science history. Nicolaus Copernicus, Gregor Mendel and Lemaitre to name a few. In addition, many priests are involved in science today. “It’s the biggest cultural myth around.”

Leading atheist scientists have helped build this myth by trumpeting the notion that faith and science don’t mix. Now, it’s up to Catholics to dispel this myth. Thanks to Templeton Foundation grants, seminaries across the country have added science courses to their curricula, with two courses upcoming at Kenrick-Glennon.

“I would say our competition has a 20-year head start on us,” he said. “They’re very slick and, unfortunately, the media has chosen to make them their darling instead of us.

“The evidence (in science) favor us. Not them. You’re not unreasonable or irresponsible to have faith in 21st century.”

Magis Center

Jesuit Father Robert J. Spitzer is the president of the Magis Center, which shows the connection between faith and reason in contemporary astrophysics, philosophy and the historical study of the New Testament. According to its website, Magis Center provides rational responses to false, but popular, secular myths.

Father Spitzer has written eight books, appears weekly on EWTN in “Father Spitzer’s Universe” and is a former president of Gonzaga Universty in Spokane, Wash.

For information, visit magiscenter.com

Galileo:early observer of universe

By Dave Luecking | daveluecking@archstl.org | twitter: @legacyCatholic

Jesuit Father Robert J. Spitzer describes famed Catholic scientist Galileo as “the poster boy for Church persecutors” who portray the Church as anti-science.

In that sense, the Church still is paying the price for missteps with Galileo in the 17th century, leading to the anti-science myth when “just the opposite is true,” Father Spitzer said.

Just as Catholic cleric Nicolaus Copernicus had done about 70 years prior, Galileo advocated heliocentrism — the earth revolving around the sun — in the early 1600s. At that time, geocentrism — the earth as the center of the universe — was widely accepted by not only the Church but leading scientists of the day.

However, heliocentrism was just a theory that Galileo nonetheless presented as fact contrary to promises he had made to his friend, Pope Urban VIII.

“Let’s face it, Galileo brought some of misery onto himself, because he made a promise to the pope that he was not going to publish the data about a heliocentric universe as a fact,” Father Spitzer said. “Copernicus had already posited it as a theory, but (Galileo) wasn’t going to posit it as fact until he had proof for it.

“The proof came several hundred years after Galileo when we finally developed a technique called ‘steller parallax,’ which was the proof of the heliocentric universe.”

Galileo agreed to abandon heliocentrism as a potential theory after the Roman Inquisition of 1616, but he went back to it definitively in 1632, publishing “Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems.”

“The fact was there weren’t any facts,” Father Spitzer said. “He broke his promise to the pope and, on top of it, made a character in his work obviously the pope, The Fool. When you call the pope a fool and break your promise to him, you’ve got some culpability.”

The Roman Inquisition of 1633 found Galileo guilty of heresy and sentenced him to house arrest at his Villa in Florence, Italy, which was the extent of his punishment. Notably, he wasn’t jailed, tortured, beheaded or otherwise put to death for his heresy.

“They just didn’t want him to publish,” said Father Spitzer, noting the culture then was much more restrictive than today.

The Church ultimately accepted heliocentrism and ascribed to Galileo’s position that the Genesis creation story isn’t a scientific treatise, a literal interpretation of creation. Nearly 400 years after the fact, St. Pope John Paul II acknowledged Galileo’s contributions to astronomy and science, plus the Church’s mistakes in censoring him.

Despite the events in the early 1600s, Galileo remained true to his Catholic roots even in death. Galileo considered the priesthood as a young man, his two daughters entered consecrated life as religious sisters, and he’s buried in a place of Catholic honor, the Basilica of Santa Croce in Florence.

Vatican Observatory brings faith and science together

By Dave Luecking | daveluecking@archstl.org | twitter: @legacyCatholic

The Church’s interest in astronomy and science dates to the late 1500s when Pope Gregory used scientific data and calculations as the basis for the Gregorian calendar.

Since then, popes have had multiple observatories study the heavens: the Observatory of the Roman College, the Observatory of the Capitol, two on Vatican grounds and the two current ones, in Italy and the United States.

The Vatican Observatory headquarters is in Castel Gandolfo, about 16 miles southeast of the Vatican. The palace at Castel Gandolfo was the summer home for popes before austere Pope Francis stopped using it for that purpose and had it turned into a museum.

Society of Jesus (Jesuits) priests and brothers oversee the Vatican Observatory, with Brother Guy J. Consolmago as the director and Father Paul Mueller as the administrative vice director and superior with the observatory’s Jesuit Community. The Jesuits share space with the headquarters in a renovated convent on the sprawling Vatican property, once the summer home of Roman emperors.

Just as it was two millennia ago, Castel Gondolfo is the summer escape from Rome, with cooler temperatures and lakes created by volcanic craters.

Castel Gandolfo features four telescopes, two on top of the pope’s home and two in the papal gardens. Visible from 40 miles away, the telescopes on the pope’s home are “a nice symbol about the compatibility of faith and science,” Father Mueller said.

Unfortunately, light pollution from Rome inhibits observation of the stars at Castel Gandolfo — the reason the observatory was moved there from Rome in the first place — so most of that work has shifted to the United States at the state-of-the-art Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope at Mt. Graham, Ariz.

According to Father Mueller, the advanced telescope was the first in the world to incorporate a new mirror technology “which has the advantage of being much lighter than previous mirrors and having a smoother front service, and being able to be steeply curved great advantages for a telescope.”

The Arizona facility, which is about three hours north of Tucson, was built in 1993, figurative light years before the digital revolution. Yet, the telescope has been upgraded to 21st-century stardards with new technology in general and with robotics in specific. Robotics first allowed remote, real-time observations from locations around the world and now allows multiple users per night via pre-programmed instructions. Individuals signing up for a specific night with the telescope and performing all observations at the site are a thing of the past, thanks to a $300,000 grant from the U.S. Papal Foundation that helped modernize the equipment.

“It keeps that telescope up-to-date, more use-able and more functional,” Father Mueller said. “With robotics, you can share the telescope more effectively.”

The modernization extends the link between faith and science well into the future.

>> Vatican Observatory

Learn more about faith’s link with science at:

watch a video on The Seven Wonders of TRAPPISt-1

RELATED ARTICLE(S):

Recent headlines about the TRAPPIST-1 solar system and its seven Earth-sized planets have created quite a buzz among astrophysicists, astronomy lovers and the general population. Surrounding a dwarf star, the … Faith and science closely linked

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.