School suspensions seen as part of ‘pipeline’ to prison

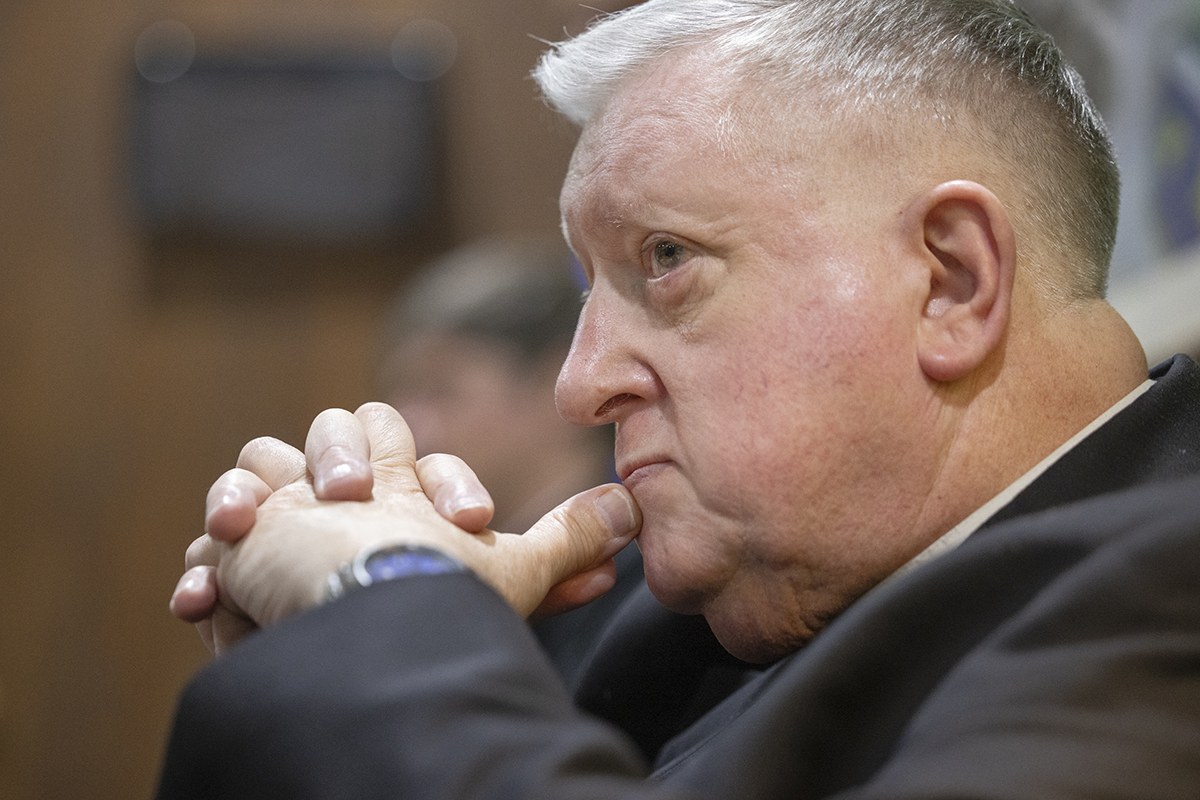

Billy Harris grew up in southwest Missouri and started getting into trouble with the law at age 14, receiving unsupervised probation for providing a license plate to his half-brother after he escaped from jail. Harris said that he didn’t learn anything from the encounter with the criminal justice system, and no one seemed to take an interest in his future.

His experience in school was similar. “I had a lot of suspensions. I got expelled for an entire half of my freshman year,” he said. “I was in trouble from an early age. The school system didn’t have anything set up to counsel me. They didn’t even try to reach the core issue of the problem.”

Harris began to get involved with drugs at 14, dropped out of school at age 15 and participated in the beating death of a man at age 16. He was sentenced as an adult, and served 15 years for the murder reported as retaliation for the man raping a friend. Harris came to St. Louis to work in construction in 2002, went to school and now works as information technology coordinator for St.Louis Effort for AIDS. He also became a tireless campaigner for his sister, Lisa, with the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. Lisa, 17 at the time and now 47, is still in prison for her connection with the beating death.

Harris said he had a period of self-reflection after about eight years in prison — including time in solitary confinement for being caught with marijuana — and decided to change his life. He was helped by a drug-treatment counselor in prison and a peer-run treatment program that teaches participants how to develop skills to lead a positive life.

Harris’ story is an example of the school to prison pipeline. That pipeline is described by Legal Services of Eastern Missouri as practices within the education, juvenile justice and criminal justice systems that create a path from school to prison. It has greater effects on students of color and students with disabilities

The Civil Rights Project at UCLA reported in 2015 that “the state of Missouri now ranks No. 1 in the nation for having the largest gap in the way its elementary schools suspend black students compared to white students and fourth in the nation at the secondary level. Statewide, elementary schools in Missouri suspended 14.4 percent of their black students at least once in 2011-2012 compared to 1.8 percent of white students.”

Metropolitan Congregations United, the Shut It Down Coalition and others in St. Louis are calling for strict limits on suspensions and say students, teachers and administrators can resolve conflicts through tools such as peer mediation, restorative student court and restoration rooms.

St. Louis Public Schools, Maplewood-Richmond Heights and other school districts have listened and instituted changes. Instead of suspending students who have been in fights, for example, they are referred to mediation once things have cooled off, with a goal of exploring what caused the fight so that it doesn’t happen again. Suspension often means an eventual return to school to rekindle the conflict.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that the prison population has gone from about 500,000 in 1980 to 2 million today.

Norman White, associate professor of criminology and criminal justice at St. Louis University, said those statistics show changes are needed in the way society interacts with children, especially at schools. Zero-tolerance policies in schools began in the 1990s, he said, as a result of violence in schools. But that quickly encompassed not just violent behavior but what was judged to be any form of disrespect, White said, and led to increasing numbers of suspensions. The change is one in which child-like behaviors are responded to in an adult manner.

“When kids are suspended from school and pushed out into the streets they become visible to police and others in ways that lead to becoming arrested and into the (criminal justice) system,” White said at a program earlier this year in St. Louis sponsored by the archdiocesan Peace and Justice Commission, Criminal Justice Ministry, SLU and others.

A project White led at SLU looked at the early years in school, when children begin to get in trouble, and worked with educators in addressing that. He pointed to the UCLA study which showed that St. Louis led the nation in suspension of preschool and elementary age children. “The pipeline is filled by kids experiencing schools in such a way that they experience hopelessness and despair early on and are not academically successful,” he said.

The schools are only partially at fault, he said, because the situation is often tied to extreme poverty. Children often experience much trauma before even entering school, and that also makes it difficult for them to succeed.

Harris, the advocate with the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, said the proper support, guidance and therapy in schools would help. “A fist fight in school is now criminal behavior,” he said. “They can arrest you and take you to jail. That creates a snowball effect that almost always happens after that. You’re taking kids out of school for a while, away from their studies, and putting them in an environment that teaches them more bad behavior rather than addressing the behavior in the first place.”

Corrections system overloaded

An estimated 6,741,400 people were supervised by adult correctional systems in the United States at the end of 2015, the Bureau of Justice Statistics announced in December of 2016. About one in 37 adults (or 2.7 percent of all adults) in the United States was under some form of correctional supervision.

Offenders supervised in the community on either probation (3,789,800) or parole (870,500) continued to account for most of the U.S. correctional population in 2015. Probation is a court-ordered period of correctional supervision in the community, generally as an alternative to incarceration. Parole is a period of conditional supervised release in the community following a prison term.

At the end of 2015, an estimated 2,173,800 people were either under the jurisdiction of state or federal prisons or in the custody of local jails in the United States.

Local response

Shut It Down is a collaborative initiative of nine philanthropic funders led by Norman White of St. Louis University. The project provides education on racial equity and implicit bias for school personnel to address the rate of suspensions for youth attending St. Louis Public Schools grades K-8. This approach addresses the issue of high suspension rates for African-American children with the long-term goal of altering current policies that contribute to the disparity. White and his team work with schools to examine how racial inequality creates barriers for students to succeed because of individual, structural and institutional bias.

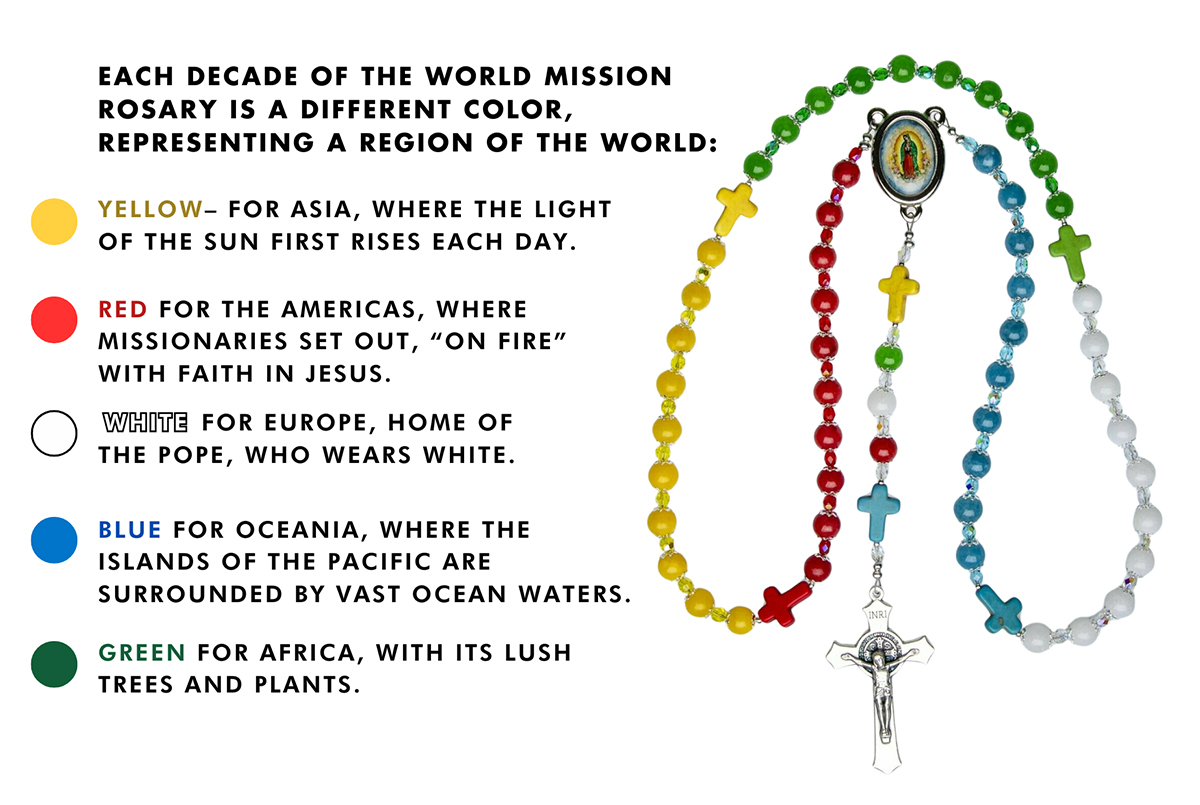

Catholic schools in the archdiocese use virtue-based restorative discipline (VBRD) as a response to bullying and bad behavior. A student who changed his behavior described it as “people who try to help you do better” and sees virtues as actions “that allow you to be more like God and closer to God.” Restorative practices address the underlying social causes of bullying, help teachers analyze structures of discipline and create a just disciplinary policy that supports Catholic social teaching.

RELATED ARTICLE(S):

Billy Harris grew up in southwest Missouri and started getting into trouble with the law at age 14, receiving unsupervised probation for providing a license plate to his half-brother after … School suspensions seen as part of ‘pipeline’ to prison

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.